If You Escaped Nazi Germany, What Would You Do with Your One Precious Life? At 88, Edith Hillinger Is Still Making Art

We rush to visit Edith Hillinger at her garden studio inside the West Berkeley house she built in the 1990s. Hillinger is 88 years old and studied at New York’s Cooper Union College in the 1960s. She draws from her childhood experiences as a refugee in Ankara, Turkey, to create obscenely masterful full-scale collages and paintings. She quotes Rilke! She tells us about fleeing Nazi Germany, her marriage, the women’s movement (and how it helped her get a divorce), and what it’s like to be an accomplished female artist in her later years. We fête her.

Edith's website

Edith on Wikipedia

Edith on Instagram

Read more about Edith's father, Franz Hillinger, on Wikipedia

About White Terror in Hungary

Take a look at the Women in the Arts Foundation

Find out more about the Bay Area Women Artists' Legacy Project here

Beautiful Online Thing: Dante's Divine Comedy by camerAnebbia

Music at 6'50" and 18' is from the album The Long Embrace by Vega Victoria

Listen to the episode

Transcription of Edith's interview

Abbreviations

EH - Edith Hillinger

JB - Jozefien Buydens

SV - Svea Vikander

Voiceovers are italics

—

[music]

EH: I’m Edith Hillinger and I am a Bay Area artist, now in my 80s, and I’m being interviewed by two very lovely ladies

[music]

JB: Svea and Evie came to pick me up and we were already running late. We reached the gate with the number of Edith’s house and we couldn't open the gate, because there was like this sophisticated lock installed on it. We were there like: “Oh my God, what is this, what is this lock, what does it do to us?”

Maybe we should try it from the inside? Try it again. Yay it worked!

I looked over the fence and I saw we were indeed at the right gate because Edith’s name was written on the second gate. It was kind of like: “Okay, if we open the first gate then we have to open the second gate!”

SV: it was double locked!

[laughing]

SV: Maybe it’s just because we’re in a rush, but it really seems like knocking at the, at the…

JB: …heaven’s door?

SV: No, like knocking at Baba Yaga's Hut. You know Baba Yaga?

JB: No…

SV: Baba Yaga is this Eastern European witch figure.

JB: That sounds cool!

SV: She’s like a witch, trickster, but she lives outside of town in the forest and you have to go to her hut and then knock on her door. Then she comes out and like destroys or helps you.

EH: Hello!

SV & JB: Hi, good morning

SV: I’m Svea

JB: I’m Jozefien. Nice to meet you!

EH: Nice to meet you. And, this is your daughter? Hi, little one.

SV: This is my daughter. Will you say hello?

JB: She was very welcoming when we arrived to her house, so, she warmly welcomed us. So, you actually enter in the living room, then you walk through a little bit and then you go to the right and then we entered her very bright, very new art studio.

EH: I built this house in 1992 with JSW Architects, they designed it, but I just added this studio. This was a 27-foot high-ceiling, so, I just ran the upstairs floor across.

JB: oh!

EH: I don't know, it seemed like so simple to just get a second studio out of that 27 foot high, so I did it and it didn't cost much.

JB: Do you work here too? Are you working on those pieces right now?

EH: Yes. And that one there is a monotype with chalk and then I'm starting to work on a piece…

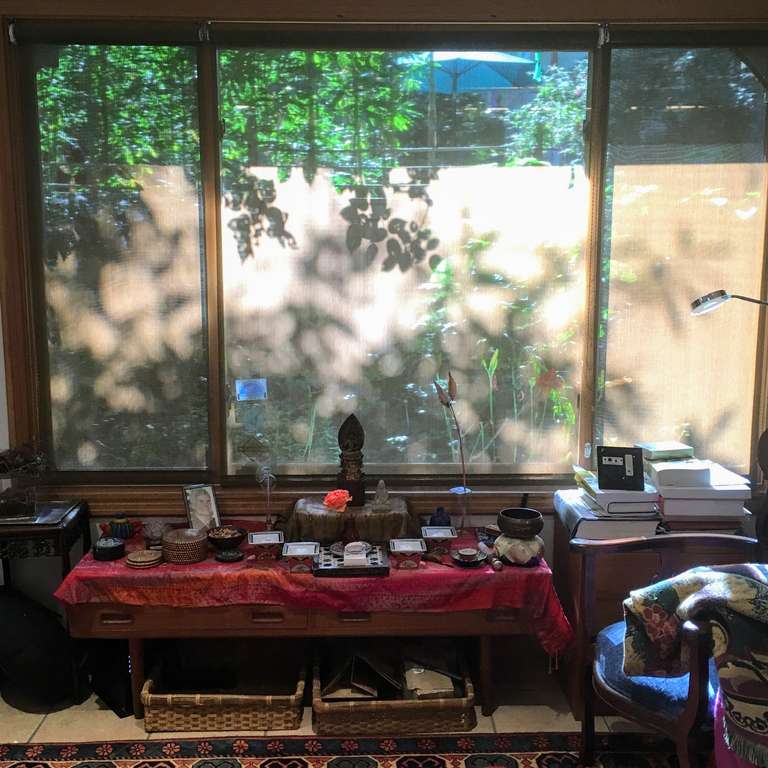

SV: Some of her bigger pieces are on the wall and she had like a large table, or set of tables, in the middle and an easel near the window.

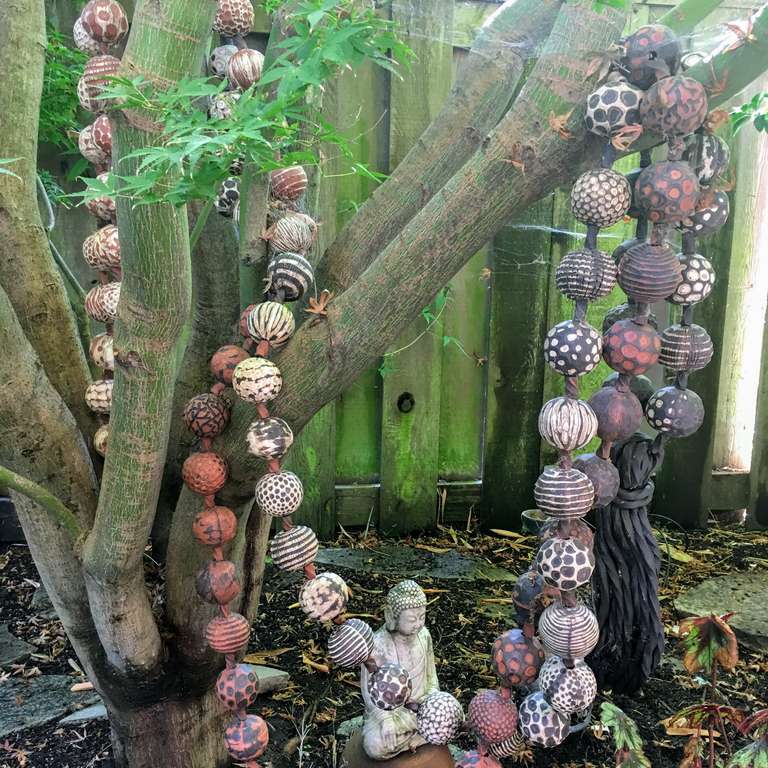

JB: She was doing the monotypes as well on the table. I also thought the windows were so big. The garden really came in to the house or into the studio, so, you have like this calm garden that comes into your house.

SV: That's true and I think, I guess having two gates which cannot be unlocked can it make you feel safer to, right, so then you could leave your doors and windows open all the time

JB: Yeah, definitely.

EH: When my ex-husband and I first moved here, we bought a house with two lots. We sold the corner lot to get some money and then we started to build a friend's house and then I got divorced and then I continued this process to built this house.

SV: You get the sense that rooms and space are really important to Edith. Her ex-husband tried to be an architect and her father was one.

EH: My father was born in Hungary in 1895, in Nagirabat, that's a small bordertown with Romania. It keeps going back and forth, it's called Oredeia when it’s in Romania and Nagirabat when it’s in Hungary. And, he wanted to study to become an architect, but when he was ready to go to the university there was some sort of uprising and it was blamed on a Jew, Bella Kun, it was called the White Terror and I think about 5,000 people died and so, the University made a quota system for Jews, so he could not really enter the university in Hungary and he emigrated to Germany to study architecture. He was lucky, in that way he ended up working with Bruno Tout.

[music]

EH: Bruno Tout is one of the giants of modern architecture and he was my father's mentor and he played a large role in, later on, in saving us from the death camps of the Nazis. So, my father came to Berlin and he was a very poor student, poor money-wise not otherwise. He needed to rent a room and he found a room with my mother's parents and that's really how they met, in Berlin.

My mother's parents were fairly poor people, in terms of money, and her father was a Singer sewing machine repair man who bicycled to people's homes to repair sewing machines, so, that's how my father met my mother and he became a German citizen. Everything seemed to be going well, my brother was born in 1930, I was born in 1933 and then off course the Nazi thing happened. And, my father being Jewish, we needed to flee, otherwise my mother wrote at the time, she thought we were going to fall into an abyss and all of us die, which would have been the death camps.

Well, by now, Bruno Tout had left Germany. Attaturk, who was then the president of Turkey, was inviting people who were fleeing Germany and Austria to come and help him build modern universities. So, when Bruno Tout got there, he heard that my family had not been able to find a way out of Nazi Germany and he asked the Turkish government to invite my father as an architect. I still have his letters and telegram that says: “Come immediately, family can follow in 3 months”. So, he went, and our family found a way out of Nazi Germany, we were very lucky, that way.

And the next 11 years of my childhood were mostly spent in Istanbul with two years in Ankara. I think this kind of fleeing and immigration is very difficult for adults, but it's not necessarily a bad thing for children, because you gather many things from foreign culture: beautiful imagery and all kinds of colours. In fact, our living room in Turkey was sort of an incubator of the artist I was to become.

It had my father's design Bauhaus furniture and then I had Turkish rugs and we had a glass front bookcase, is where the glass from rolled on ball bearings to open, and I loved those bookcases because they had our inheritance from Bruno Tout’s time in Japan. They had wonderful gold flagged fans and all kinds of children's toys made out of lacquered paper and I really love sitting in front of the bookcase and just admiring all these works. That's where my love of Japanese paper comes from. Its very beautiful and I use it mostly in my collages.

JB: From the room her father rented to the living room in Istanbul, Edith has a keen eye for architectural elements. You can see it in her collages, which are inspired by the mashrabia of the Middle East.

EH: The collages, they really have to do with the Islamic background and the many patterns that I saw when I was there. Islamic architecture is very much decorative in many different ways, in mosaics and wrought iron and many different ways. So, I was inspired by all those patterns that I saw in carpets, in textiles, in mosaics.

Many of these monochromatic drawings like the one there on the right and the one on the lower right, this all started one day when I was cleaning up my studio I came across a photograph I had taken in Spain at the Alhambra, and it was one of these screen windows that Muslim women often sit behind so they won’t be seen, and I started to draw a lot of patterns. And, then I draw them on a big sheet and cut them up into a collage. The difference between drawing and collages, usually with drawing you have an image in the mind, but with the collage you just shuffle your papers around and see what happens.

[music]

EH: I often work with pressed plants. When you press a plan it's like an x-ray the inner veins come out.

JB: You dry petals of flowers yourself?

EH: Yeah, I have plant pressers.

JB: Okay!

EH: I press them. Rilke also said: "The process of desiccation lends the most accidental gestures of a flower, the ultimate precision of finality". This is a drawing of a succulent leaf and three stages of, of course when things dry they shrink and also, some of these leaves, like echeveria leaves, as they’re drying they turn many different colours before they become a sort of pink

SV: Do you think living in California has impacted you?

EH: That's why I moved to California. I wanted to be closer to nature.

JB: Oh, wow!

EH: The philodendrons in my Manhattan apartment were insufficient.

[laughing]

EH: They become an imaginary plant, really. This plant just looked like bandages and I painted into it. It's interesting because with immigration people who have to flee their country often can’t take very much with them and sometimes it's just a rose or something they’ve picked and put between the leaves of a book to take with them to remember. My mother picked pansies from her mother’s grave and pressed them and took them with her when she left Germany. I also remember my father finding a four-leaf clover and pressing that.

sv: At this very moment, my kid runs in from the garden to interrupt our interview to share some very important news.

Evla: Mama, I saw a squirrel up so close!

SV: You saw a squirrel up so close? Well, good!

EH: When you are an immigrant there is, there is some difficulties in terms of your roots. I think people who are rooted in one place and one culture, at least I imagine they’re having an easier time, but maybe they’re not. I think, trying to stay in touch with what is meaningful in terms of your own inheritance and past is perhaps more difficult for an immigrant than it is for somebody who stays rooted in their culture from beginning to end. It is something I'm struggling with, what is meaningful in the world, of course the botany is universal, so that was fine and there was the collage which was my Turkish background. Now I'm not sure where I'm going.

[music]

EH: Cooper Union was completely free, you had a full year of completely free education without any tuition.

JB: Wow, that’s amazing!

EH: Which is not the case now, but they’re trying to get it back. The way you got into Cooper, what you did was you went for three days and you sculpted, drew, painted and they judged you on what you did there and that's how you got in. I was never very precise and the courses I did not do well in were calligraphy—I was very bad at calligraphy, I couldn't hold the pen steadily at 45 degrees and also, I would usually misspell the word. The other thing is that, the student who excelled at calligraphy committed suicide and that was not encouraging to me, I don’t know.

I was there from 1960 to 1964, that was before the Women’s Movement in the arts. We started in 1970 in New York, anyway, and I joined women in the arts as much as one of the founding members and we had our own gallery at Greenwich Village. People like Louise Nevelson came down to be very supportive of us and support younger artist. Georgia O'Keeffe was never interested in supporting, other than…

JB: I think that if Edith wasn't a woman she would be more famous as an artist, because she was working in the sixties and seventies and then, and the 50s, and then women artists weren’t as valuable as men artists were.

EH: At that time museums and galleries weren’t really showing women artists at all, really. It’s still much more difficult for women artists in terms of their legacy, because, they are being less collected by museums and major collectors are mostly male and are mostly collecting male artists and so, women’s art brings less money, and less money means, and being less collected means, that it's much harder for women artists to save their legacy after they die. Much of women’s work disappears, really.

SV: She talks about how, at this point in her life, the biggest drawback of that isn't “Oh, I could have, I could make more money or more people could know about my work”, but the—what happens to a very prolific, very talented female artist at the end of her life, like, who is going to take her work, where is her legacy going to go? I think that’s, I’ve never thought of that before.

JB: No, me neither actually, me neither.

EH: … parceled out between the family and it goes away. So, I founded the Bay Area Women's Artist Legacy project some years ago and we're about 30 artists and I think we are gonna do a book about our work, which will be very nice. And, we have had inquiries from other artists who want to, who also found chapters, so this may happen.

SV: Is there a website for the… I know there is.

EH: Yes, there is. B A W A L P. Bay Area Women Artist Legacy project

SV: While the women’s movement didn’t manage to get Edith’s work preserved in the way that it should be, it did help her to get out of an unhappy marriage.

EH: Even though Larry and I fell in love, it wasn’t a good marriage. We were not well suited to each other and then, the women’s movement happened and we got even less suited to each other than we were before. What happened was that, Larry didn't have very good people skills and that hurt him in terms of job success, you kind of need people skills and he came from Israel, from a not a very well off family, I think his father may not even have been literate, he was a house painter. Although, his brother became a very successful maritime lawyer.

When I met him in Manhattan at a singles thing, he was doing office interiors, designing office interiors, he had studied architecture, but he never got a license for it so he did interiors where you don't have to have the architecture license. Then, in the mid ‘70s I got a residency at Los Gatos for the Arts. So, I came out and he came out with me. I got divorced around ’92 and then I built my house that time. I was much happier after my divorce, I just wasn't happy in the marriage and so I felt very free. Very good.

[music]

SV: I ask Edith how much of her early childhood and the trauma of immigration is still with her.

EH: Well, I think is lessening, I think I'm going in some other directions now that are more current. I’m becoming interested in celestial bodies. It’s a way of perhaps coming into the present in a different way and maybe I’ve, I have exhausted the past. I'm not sure. At least what I can do right now with it.

SV: I think maybe part of that is related to her meditation practice.

EH: I open my door at 7:30 and the meditators come in

SV: Really?

JB: Oh, so that was this morning?

EH: This morning we had meditation.

JB: Okay, alright!

SV: How many people come and where do you meditate?

EH: Well, it depends, this morning there were four other people. Sometimes it’s six or eight. My living room isn’t all that big, but, that's about it. It’s a silent meditation. What I do is, I set up the altar, I put fresh flowers and light the candles and when people come in I start the timer and when the half hour’s off, the timer goes off and then I say a few words.

SV: Can you share with us what you said this morning?

EH: What I said was: “We dedicate the merit of this practice to all sentient beings. May they find happiness and be free from suffering”.

[music]