Is Your GP Secretly an Artist? Lorraine Bonner on Healing With Clay

Onward! To East Oakland where artist-physician-writer Lorraine Bonner sculpts clay in the house that was once her mother’s home. Lorraine shows us the space, now converted completely to a studio-gallery, and talks about growing up in Queens, moving to rural California in 1970, moving to Tanzania with her husband so they could have their baby in an African socialist country, and studying Medicine at Stanford with two small children at home. Bonner’s work addresses personal, societal, and environmental traumas including racism, abuse, and torture through figurines and abstract shapes. How does she navigate such heavy topics without buckling under their weight? Why doesn’t she want to be a doctor anymore? What does it mean to “redeem” the colour black?

All this and more. Plus cat.

Lorraine Bonner's website

Follow Lorraine on Facebook

Find out more about the East Bay Open Studios

Beautiful Online Thing: the Rhoda Kellogg Child Art Collection

Listen to the episode

Transcription of Lorraine Bonner's interview

Abbreviations

LB: Lorraine Bonner

SV: Svea Vikander

__

LB: I grew up in New York, yeah, in Queens, just like the [former] president. Only slightly different part of Queens. I moved out of Queens to go to school in Boston and Cambridge. And then I came here in '70. I had graduated and I was kind of, just kind of drifting a little bit. And I met this guy who had just come from California, driving cross country with his friend and they were about to go back. And I said, "You know, I’ve been thinking a lot about going to California, what if I come with you?" So we all drove cross country and came back here. We lived on Sonoma mountain for a while. From Sonoma we went to Africa, Tanzania. I was pregnant, we had our baby in Africa, in Tanzania.

SV: Oh, wow!

LB: Yeah. So. We wanted her to be born in an African socialist country. At the end of the year we were running out of money and we had studied Swahili, we e en took the, civil service Swahili exam. If you wanna work, because it's the national language, you can't just be monolingual in English, you have to be able to speak Swahili. And we passed it, and we were thinking, “Oh we could get a job teaching English, we could do something. “But you know, it felt like we really had a responsibility for here. You know. This is where we really need to do the work, we can't go over to somebody else's country and kind of glom onto them. We had an obligation to come back.

And that was when I decided to go to medical school down at Stanford. And he decided to go to law school. I was really interested in mind-body medicine. And I had started meditating while I was in medical school. And when I got out of training I started studying hypnosis and guided imagery. And so I started working a lot with people that had chronic pain and chronic illness. Including some of the people who, when the chronic fatigue syndrome mini-epidemic was happening, I mean, I saw people with that. And didn't make them feel like they were making it all up. I was kind.

I finished all of my training in '78. You know, I had two kids by then. I had another kid when I was in medical school. And then in '79 my husband passed the bar and we decided to go get an office together. We had an office in the Tribune Tower, the Oakland Tribune! Yeah! At the very top, there was the 17th floor, it was right above the letters. Beautiful views.

I actually left that office in '85, I split up with my husband. I got another office that was closer to the hospitals right across the street from what used to be Providence and I was there for three years and I was trying to put together a multi-disciplinary pain practice and there were maybe 4 or 5 other women that had different modalities, physical therapist, somebody that was doing Trager, somebody that was doing acupuncture. And we had this vision of opening a multidisciplinary pain centre but you know, we were way ahead of our time. And there's no funding for anything like that.

And around '89 or '90 I started, I sold the practice and started working as a hospitalist. Which is like an internal medicine in the hospital. And around that time also I started doing art. After I started doing more of the artwork, and got excited about it and actually had this delusion that it might actually make me some money—which has proven to be a delusion—I decided to spend more time at it. And so I cut back and started working nights.

And I was only working like maybe one or two nights a week. And it was a lot easier to manage. And so then I had time during the day to do more work. It still didn't make any money but…[laughter].

I kind of always felt when I was doctoring that it was really kind of incomplete and kind of temporary and because I had had a kind of, both a political and a kind of spiritual understanding of the world, even before I got into medicine, I really understood that what I was doing as a doctor wasn't complete. It was just treating one small section of a much larger organism, which was not just the person in front of me but also the whole social structure around them and the spiritual reality that had been so deformed by the political and economic system.

And the art enabled me to, to kind of bring those together. To bring that individual body…I was working with clay, which is like, what we're made of, you know? And at the same time, working with also concepts of political and spiritual largeness...

[music]

LB: I never thought I was an artist, I always thought that was something that was completely beyond me and other people were artists and I was a scientist. The thing that got me into art was that I was, started to deal with a lot of trauma. My childhood trauma and this goes into the therapy side of things but in the '80s a lot of people were recovering memories and I was one of those people.

The memories were really pretty horrible and a friend of mine was taking a ceramics class at one of the community art centres and I used to go over to her house and we would fiddle around. And then she gave me a bag of clay and I started making these little people. And these little people just started coming out of my hands. And then these images and these scenes, and I was astonished and didn't know where it was all coming from.

And I understood that it was important. And so there were two things: I wanted to enable this to continue and I wanted to get better at it. I wanted to get more skilled. And so I kept doing it and then I started going up to Merritt College and took some ceramics classes up there and then I started taking—first I was just taking their basics ceramics class, but it was mostly around pots, and I wanted to do sculpture. Then I discovered there was a ceramics sculpture class up there taught by Susannah Israel and so I started taking that, I took several years with her.

And that was when I started realising that the work was not just about me but that it was about the whole planet. And the themes of plunder and lies and force and violence that were my personal story, was also the story of (which I always knew) this country. They ripped it off from the Indians, they tortured people, they murdered people. The African slaves, all the ways that immigrants had been treated before they lost their accent, got turned white, you know. I don't usually show those little early pieces. I used to in the very beginning.

I think probably the first time I showed with East Bay Open Studies I showed some of those and they were just too much for some people. Even some of this work which to me seems pretty tame by comparison, is too much. You know, some people can't even look at them. They just walk past them and sort of look away. And some people wanna know about them, ask me about them. And some people just clearly are stricken and even cry sometimes…

[music]

LB: The sort of core of the Perpetrator Series is actually in a book form with written material around it. And that's mostly all work that's in this black clay called, uh, Cassius. Cassius Basaltic. And those pieces are specifically about calling attention to the fact that we're born with the expectation of trust. We're born expecting that we can trust everybody. That is a really fundamental truth. But there are people for whom betraying trust is ok, it's even a source of pleasure. And those are the people that I define as perpetrators. People who betray trust.

And because of the way things are set up, it's very hard to actually see those people unless you're being perpetrated against yourself. And in that case when you bring your testimony about the perpetrator to the public, nobody believes you. It's just like domestic violence was completely invisible. And then it was the woman's fault. And even now, if you go to an emergency room, they may ask you—in fact they're obligated to ask you—if you're bieng hurt, if anybody's hurting you at home. But they don't ask the perpetrators: are you beating up your wife? Are you treating your kids inappropriately sexually? They don't ask that because nobody sees them.

Nobody believes it, even if you tell them, they don't believe it. That's kind of the idea of the Perpetrator series, is to remind people that if you're feeling beaten up, you did not beat yourself up. Someone beat you up. And that person is the person who needs to have attention drawn to them. The person who's actually doing the harm. It's about the perpetrator. It's not about us victims.

And I don't mind using the word “victim.” I know a lot of people are very offended by the use of the word “victim.” But I think that if you don't use the word “victim” you're making the perpetrator invisible, you're acting like, "I have to survive and thrive even as I'm continually being beaten down.” As if the beating down isn't happening, as if I'm on the ground of my own free will.

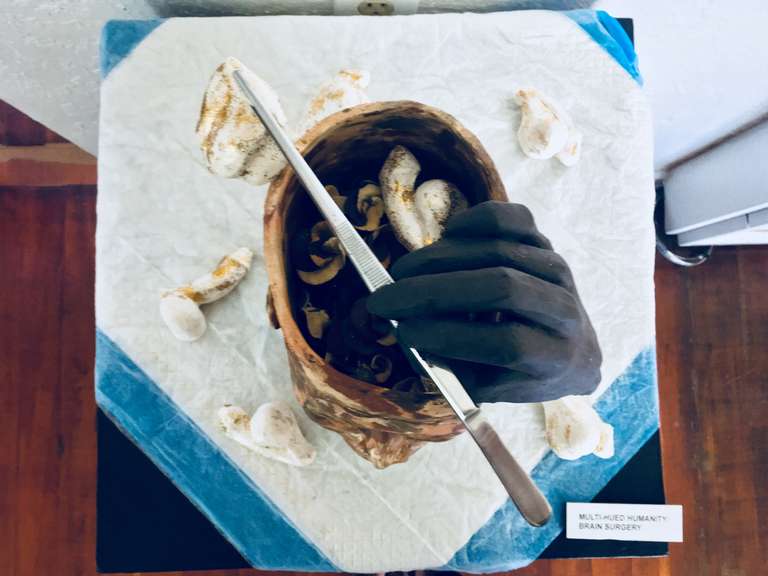

When I discovered this black clay and I started making images in it—and actually it was even before that—the perpetrators were always in white. There's a white clay that I use that has a very similar shrinking compatibility (technical factors!) that work well with the black clay. Most of them have some kind of combination of the black and the white. So the perpetrators are basically expressed in white and the good guys are expressed in black. That then also became part of the whole redemption of black, which was part of the Multihued Humanity series. The "Multihued Humanity and Redemption of Black" series.

[music[

LB: So the idea is that we are all one species, we just happen to have different amounts of the same skin pigmentation, and our colours are from melanin and from the proteins of the skin, like keratin and collagen, sun exposure, the amount of visibility of the veins and capillaries and blood under the skin, how much fat there is. All of that stuff contributes to the skin colour and it's just so... stupid to try and categorise people by colour.

I mean it's just a stupid idea that obviously came about because it was necessary for the continuation of the plunder and lies and violence that underlies the structure of our social world at this time, which was imposed on people who didn't have those things but then did. My idea is to help people remember that we are all one species. And that these trivial differences are just that, trivial, no more than how tall you are, what shape your eyebrows are, something like that.

In that sense then I had to really account for the white and black thing that is such a strong meme in our culture. And looking at if we started out with a balance of black and white, how did it happen that white came out on top? And, I mean, if you really listen to language, this is something that Malcolm X talked about in the Autobiography of Malcolm X, you know. All of the things that are signified by black and dark and are all like ugh, yucky, evil, bad, “we don't want that,” and all of the things that are associated with the colour white are holy and spiritual and pure. It’s not like that to me.

This is just me and my understanding of spirituality. There is a balance there and the Yin is just as important as the Yang and the cool feminine is just as important as the white hot male white. So that's kind of the balance that I'm trying to encourage people to think of Black and White not as skin colour but as archetypes that actually are co-equal with each other.

[music]

SV: So in terms of your studio space, this house used to be your mom's. Do you still feel her presence when you work here?

LB: Sometimes I talk to her.

SV: I'll take that as a yes!

LB: I like every part of this space. I love it that it gets so much sun, I love the fact that I have a little kitchen and if I do wanna eat something I have a little frozen Trader Joe burrito in the freezer, you know [laughter]. I love the gallery space, I love the light. I love my cozy room. It's just so nice. The only thing I would like is more workspace. Which, you know, that's just a trap.

Because when you have more workspace then you need more workspace. It's like the first kiln I got was like 8 inches by 8 inches, and I was happy with that and then pretty soon I was making work that was too big to fit in that little kiln. Then I had to get a bigger kiln then I got a bigger kiln and then that got to be too small! And then, you know, I mean, it just, so, although I say I'd like more space I know that it would not really work.

The big challenge for me now is getting the work out. Because I think it is important. I think that there's something about it that is really in tune with the times. The whole personal is political, the political is spiritual, the planet is involved in everything. So getting the work out, where it can be seen, is, I think, a really important thing for me to do and it's very challenging. And especially because as I see the whole emphasis is on young artists, and I can't claim that anymore. [chuckle]

What I'm doing right now is really trying to improve my skill. Particularly in terms of faces. I wanna make more heads. I never went to art school so there's a whole bunch of stuff that I never learned, like portraiture. I've done a few portraits but they are agonising, it just takes me forever and I never can seem to get it right.

And I'm doing some exploration of glazes and then also the heads, there's one at the house, I usually make the heads—the heads are very particular about how their hair is gonna be. Or if they're gonna have a head wrap or something. Those pieces, that part of the piece, would get glazed, either the hair would get glazed a colour. I’ve got one that has a head wrap with a little flower on it. Very cute. [laughter] Stuff I would never do for myself. But the pieces want that so, “Ok, you can have that!”