We’re on our way to Belgium! Come eat quesadillas in Tramaine de Senna’s studio with us. She’s a mixed media artist with a background in architecture, proudly from Vallejo, California. Nowadays, she loves the light and space in the Antwerp studio she shares with her husband. It has a band saw and a paint dryer and a sewing machine and a huge jar of beads that’s great for looking at. De Senna talks love, absurdity, and the migration of forms. We can’t bring ourselves to leave.

Some helpful vocabulary & information:

Lichtkoepels - the Dutch word for "skylights"

Korla Pandit - born John Roland Redd, known as a French-Indian musician from New Dehli, India. He lived and played music in the USA in the 1950s

Jambi, the genie - one of the characters of the television show Pee-wee's Playhouse

European art schools Tramaine studied at:

Sint-Joost School of Art & Design, Breda, the Netherlands

HISK (Hoger Instituut voor Schone Kunsten), Ghent, Belgium

Tramaine on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tramainedesenna/

Tramaine’s website: https://sites.google.com/site/tramainedesennamfa/

Listen to the episode

Transcription of Tramaine De Senna's interview

Abbreviations

jb: Jozefien Buydens

sv: Svea Vikander

tds: Tramaine De Senna

__

jb: Hello hello and welcome to a new episode of Art Crush International. I'm Jozefien Buydens

sv: I'm Svea Vikander

jb: And together we take you into the artist studios of the world. Because these artist studios are just wonderful places with lots of light, beautiful artworks, comfy chairs, and lots more. Svea, where are we going?

sv: Today we're going to Antwerp

jb: In Belgium!

sv: That's right. Have you heard of this place called Belgium?

jb: Uh, yes. I have heard of the place called Belgium because I'm Belgian, I was born there, I grew up there.

sv: Yeah it's a really nice place you should go there sometime. But today we are going to visit the studio of Tramaine de Senna

jb: That's so exciting, can you tell us a bit more?

sv: Tramaine, Tramaine de Senna is your friend,

jb: It's my friend, it's true, but you can introduce her!

sv: I'll talk about her, yeah. So your friend Tramaine de Senna, who lives in your country, Belgium, also has roots in the Bay Area and she's a visual artist. She does sculpture and textile work. And you can find her on Instagram at @tramainedesenna. [spells out] And yeah, she's really wonderful and she has a studio in Antwerp and she can also talk about her experiences in the Bay Area as well. So we're gonna get a really interesting compare and contrast today.

jb: I've been really looking forward to doing this interview with Tramaine so, we'll have a blast.

sv: That's right

jb: Ok

sv: The ceiling can't hold us

jb: No, they can't, they can't. Shall we hop on a plane, to see Tramaine?

sv: Let's go!

tds: I'm Tramaine de Senna, an artist living in Antwerp, Belgium. But I'm proudly from Vallejo California.

jb: I drive the car to Tramaine's studio, which is located in Deurne, one of Antwerp's suburbs. Even though I only need to drive for 35 km, it takes me almost 2 hours to get there. As everyone in Belgium knows, Antwerp has a huge traffic problem. So I should have seen this coming. I park the car in the parking lot and go look for Tramaine.

There are a few studio spaces on the property, as well as a beer cellar. Two employees are standing outside the shop looking at me suspiciously. I can see them thinking Who is this woman and why oh why is she carrying around a huge old fashioned cell phone with a fluffy hat. Note: the old fashioned cell phone? That's my recorder. And the fluffy thing on top? That's the windshield. So I don't catch loud windy noises when recording outside.

I feel like I'm being watched so I smile, nod to say hello and keep on looking. When I can't find the entrance to Tramaine's studio, I give her a call.

tds: (over the phone): this is Tramaine!

jb: Hi Tramaine, this is Jozefien. Um, I'm here.

tds: Hi, I'm gonna come right down and find ya.

jb: OK perfect, see you soon!

jb: Oh, hi hi!

tds: Where'd you park?

jb: Oh right there, is that alright?

tds: Yeah yeah yeah, nice to see you!

jb: Oh yeah, nice to see you again, too.

We walk up the stairs to the first floor and enter Tramaine's spacious studio on the right.

wow, my god this is a big space.

tds: I think we're lucky. Because I don't think all the spaces have this kind of light, ceiling.

jb: Oh yeah yeah yeah, yeah that's good. How do you call it in English? Lichtkoepels?

tds: Skylight! I'll show you what we have.

jb: Before we drive into our studio tour, Tramaine offers to cook us delicious quesadillas because it's already after lunch time.

You're so sweet. I'm here to interview you and I'm getting food instead.

tds: But isn't that what artist studios are like,

jb: consequently, we cozily chat our way through the afternoon and almost forget we have an interview to do! Let's get to work!

Well mostly we start at around 10 and then it's finished around noon.

tds: Oh my. You can start, I'm just gonna like cook these while I'm...

jb: No, that's alright.

[music]

tds: This is the studio,

jb: yay!

tds: Thanks for coming

jb: sure, thanks for showing me around

tds: Yeah you're welcome Like, I have a lot of art stored against the wall here

jb: we're looking [duck down more] at some wrapped artworks on the right when entering Tramaine's studio

tds: very large sculptures, large wooden panels and frames from other artworks. I think we're gonna throw away some stuff.

jb: Oh, really

tds: Yeah, and there's also paintings from other people, too. So that's nice.

jb: Moving forward, we arrive at the first of many of Tramaine's work stations.

tds: tools and a machine for drying paint which is pretty handy and a—

jb: Which one?

tds: This one, it's pretty handy, yeah yeah, it's great. It's something that you need for a studio but if you're at home it would eat up your electricity, you know? It's very practical. That's a band saw and I remember at Berkeley when I was there, there was a picture of a bloody finger detached with a little string in between it, like some kind of organ because it was like, "Do not,—watch your fingers."

jb: Important

tds: Yeah very much so. So that thing can take stuff off. So, next to the tool box just like a large work table with a lot of junk on it right now.

jb: So this is the spot where you work?

tds: actually I work across from it, I have more tables

jb: Oh wow wow wow

tds: yeah, different media. So this is like, crushing things or painting stuff. This table, taking things apart, yeah you see a whole bike chain. I gotta clean it up. Yeah.

[music]

tds: But also a small kitchenette because when you're working for a while or if you need to make glue out of flour salt and water, it's handy to have a hot plate. The studio came with the refrigerator and microwave too, so it's a pretty handy thing when you wanna put in long hours, it's nice to feel comfy actually. So yeah that's what you see and next to all of that is plenty of book supplies, just tools.

jb: Yeah, it looks very organized.

tds: Yes! You know you need a little bit of organization so you can cut loose with making art.

jb: Do you wanna show your other work table?

tds: Yes, so a little turn, this is another table that I use for fabrics, fabric work , sewing, maybe painting small objects. It's like a dry table. And it has cardboard on it right now because cardboard is really great, accessible, I can find it on the street but it's just a really great surface to work on if it's clean. So I'll just put out a cloth and then I'll do ironing and stuff, for working with fabrics that cannot get dirty. It's always this spot. This spot is always a very clean spot, you can make objects and keep it kind of pristine.

jb: And there's a huge jar with colourful beads.

tds: Yes, yeah, um, it's great to look at. I haven't incorporated it in my art yet. Oh wait actually I made a little art piece on the wall with some of these rhinestones but um, I really enjoy some of these colour combinations because they remind me of toys from when I was a kid. Barbie and the Rockers, Barbie had her own rock group...

When I look at her clothing or her tools, little guitars and stuff, they had really great colour texture fabric combinations. For instance like a neon green with a magenta and maybe some yellow in there. So with some of these rhinestones I bought them just to have fun with it, and can I show you over here?

jb: Tramaine takes me to another work station on our left to show me one of her artworks.

tds: So I made this 3D card. There's actually a second one out there that I gave to my lawyer. But I use the rhinestones to accentuate this card which is Jambie the Genie and Jambie is a character on Pee Wee's playhouse, a great TV show for children which came out in 1987 and it went until 1991 but um I love the character Genie because it's the only character on the show which is not an animal come to life or a piece of furniture that has come to life.

It's its own thing, something supernatural. And it's really great to think of this thing, this entity that allows you to make wishes and maybe they can come true. The whole show is imaginative and creative. But this one character is just -- it kind of looks creepy, the card I made, the rhinestones but it's also a little surprising reminder.

jb: and it's very sweet. and the head turns around

tds: yeah the head can turn but maybe one day I can make it into a brooch somehow. But yeah, that's jambie's head because it's a head in a box and when you say something like 'wish' the box opens and then he starts talking.

jb: And there is also this golden shelf

tds: The golden shelf?

jb: No, the golden shell, the golden shell

tds: The golden shell, yes, a girl friend of mine who's also an artist, a painter, gave this to me at the opening of the last show I had, "Supernatural" in Antwerp. She got it at a vending machine, it had a toy in it but I guess she gave it to me because the chair objects I made for the show reminder her of this scallop!

jb: Oh, I can see that

tds: Yeah yeah, I love it actually I love scallops because it's like the little mermaid—Ok, all these things going back to toys, I'm revealing all my influences but that's okay.

jb: Toys, that's important

tds: yeah yeah

jb: Oh and this, there's another desk in the corner?

tds: Yeah, there's a lot. But which one should I tell you about? Like this is the boring one, that's the exciting one.

jb: Let's go to the exciting one.

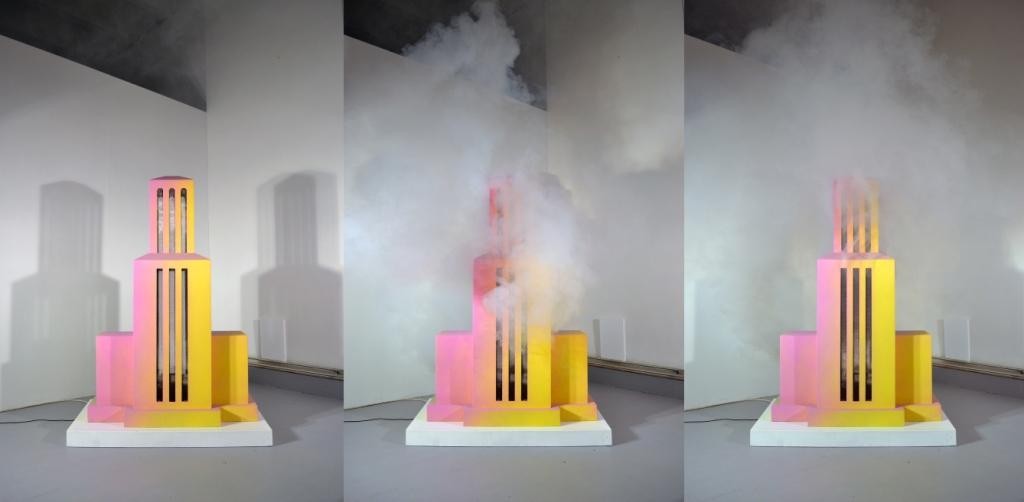

On the wall in front of us, hangs Tramaine's collection of photographs that serve as her inspiration

tds: I'm sure everyone collects images, or things that intrigue them somehow. I remember doing that in high school but also at Berkeley in my architecture studio but even now I still collect images. I hang them up above the wall to think about stuff. And they actually influence me to make objects.

But what I find, I would like to transfer the aura that these images have into an object. And that's, that's kind of like the first parts of making art for me. So yeah, it's uh, I just collect theses things that alternate between civilization, these monuments of civilizations and also home decor, or cozy things, or movie sets, or objects or toys.

jb: It's nice!

tds: Thank you.

jb: Do the pictures change over time?

tds: Some pictures I add to and some I take out but then some I keep with me for a long time. Also, images from the Wizard of Oz I've been keeping with me for the past 8 years also. Because my father likes that film, it's an influence for people but also just aesthetic-wise, it's beautiful, it's monumental, it's made in the late '30s, and the character Dorothy going on a journey, which people can relate to, going on a journey whether it's physical or not.

But her being surrounded by these three characters -- these male characters -- but they're actually symbolically different facets of her, you know? But in order to show a multiplicity of being the storyteller shows it in different characters. So I really like the idea of a journey somehow and the mystery within people.

And then, yeah, new images come in. But roughly throughout the years, I've paid attention to my archives and they just basically stay the same. And they're images that either I've taken or that I've found, took photos of, or things that I've found online too. It comes, they come back to life. Where they're being reprinted again or scanned, or printed again, or living in my computer. And then again, we have some toys here also

jb: Oh yeah, here he is, right?

tds: Isn't that amazing? Because my auntie, whenever my sister and I would visit her house with my uncle, she had all these tchotchkes in her cabinet and one of them, she would have all these toys from PeeWee's playhouse and you couldn't touch them but you could look at em, so it was like amazing, I'm sure when I go to see her she will still have those toys and I'll stare at them.

jb: Now that the studio tour is done, we set up at the kitchen table to continue our interview.

What do you like about the studio space you're in now?

tds: Oh my gosh what do I like about it? I love the fact that there is light coming in from the ceiling and you and I were talking about that. Like um, skylights? But I forgot how you say that in Netherlands?

jb: Lichtkoepels

tds: [repeats] That's what i love about it. And I've always wanted that, in the back of my mind wherever I've gone. I've always wanted to have really great natural light somehow. So I am very lucky to have this studio with lichtkoepels in the ceiling. So I like that and I like the fact that there are other people here, in this building. Other artists as well.

When I open the windows I can hear them, which is cool. But also when I open the windows there are all these, there are many rooftops that I can see. And it's kind of like in the back lot of the streets so you have—it's funny how things are set up over here in Belgium. You have the facade of houses and the entrance way of houses and stuff. But when you look closely between spaces you can see that there might be interior courtyards. Or maybe in this courtyard there's a supermarket.

But in this case there's also this back story of how people live. You see the interiors of people's houses. Not here but in other spaces. But one of these days what I'd like to do when I open these windows is to actually build a physical bridge -- it's a maybe 6 foot span to the next rooftop. And my neighbours can easily go onto these rooftops but for me there is corrugated clear roofing that shows what is underneath, which is like a beer cellar. So there is no way that I can climb onto this roof and jump onto the other roof.

Then when I don't make art I can sunbathe! In the privacy of not many people seeing me, which is great.

jb: If there was one thing you could change about the studio, what would it be?

tds: good question! I would raise the roof, like uh, make the ceiling higher. Which is impossible because this is all poured-in-place concrete. But having high ceilings is so nice, it's just a nice feeling. And it's really hard to find. You can find it in fancy chic buildings but not in studios so much. But when you do it's really great, it's a great feeling.

jb: would you store more?

tds: [chuckles] Yeah I know, huh. And that becomes an excuse to store more crap and art! Yes Josie, thank you [laughter], yes I would collect more things to store, yeah yeah. Yeah maybe, build higher shelves and store things, I guess. Yeah.

[music]

tds: The first thing, as a child you start off creating things and for me I just enjoyed it and it just stuck. And all throughout my schooling my classmates always encouraged me and my teachers did too. And my father was always concerned because he has this idea that artists always make money when they're dead which yeah, it happens! My mom always supported me as well.

My dad was wanting me to be more well-rounded so when I went off to college that, you know, it's this kind of immigrant idea that you must work hard, study hard, and go to university to get a good job so you can support your family. So I followed through with architecture but I also studied art and I went into architecture but I always wanted to make art, and I always did, but there was one person my dad knew.

It was the mother of his friend named Nancy, [name]. And she was the first person I ever met who was extremely cultured. She passed away a few years ago. She would have been maybe 80 now. She married a doctor and then eventually, she was also married to a lawyer, but she lived in San Francisco on Divisadero, and her neighbour below her was former governor Jerry Brown, you know what I mean? She was super high class.

But she, I don't know, she liked my sister and I. She introduced us to SF MOMA when we were kids. I mean, I remember she took us there and I saw Jeff Koons' Michael Jackson With Bubbles statue, and I think it was an exhibition, the main exhibition there was about drawings from kids who were abused, sexually abused, and I remember seeing her cry. And I never saw Nancy cry or be so emotional but that was pretty cool to see someone cry, viewing artwork, especially someone like her.

But she was quite a figure for me. And my mom always gave my sister and I play dough and whenever we would visit my mom we were always making stuff or sewing things. So it's just always stayed and it's just been a path of how to find my way so I can make art. You gotta do all these other things, you gotta go to school for other stuff and take jobs or whatever. But the main thing is always because I need to make art. I need to go this way because I have to make art.

[music]

jb: You went to art school from university onward or were you also in art school in high school?

tds: In high school we had art classes and stuff but I went to the University of California at Berkeley and so I did a simultaneous degree, I studied architecture but I was also in art. The silly thing was because I was in both programs, I couldn't identify with either one and I always thought well, I will never be an artist but I'll just make stuff. I didn't know how to dream.

But then afterwards when I got out and got these desk jobs, I really wanted to pursue art but I just thought I couldn't because there was no way to make a living. I worked for about seven years, working in various jobs. And I had enough money saved up to go back to school. I wanted to go to art school but I couldn't do it in the States because for me it was just a little bit too expensive at the time, and I also wanted to get out of the country for a bit just to see what was going on outside the Bay Area.

I was trying to become fluent in German for the longest time, so I could go to art school in Germany because I had exposure to Germany for a while and I really liked their schooling and the people who were there, it just—the price of food and transportation and all that stuff was really nice, and kind of modest. I was in Berlin in 2009 and I met some Dutch artists. And at that time I had finished my job at a magazine and I had applied for a residency because I was thinking, "Well why not," you know? "I need to try it." So I found a residency in Berlin.

And I met an artist duo and some of their friends and I thought, "OK, they came from the Netherlands. Where is this country? And how did it produce such quirky and amazing artists?!" So I decided yeah, I should go to the Netherlands for art school and it turns out they had programs in English as well. I studied at Sintyos (?) this was in Brega (?) in Surtoganbox (?) that's in the South of the Netherlands.

So I got my Master's there and right after I was accepted into an art institute in Belgium. In Ghent, the Hogha (?) Institute for KjonKunsten (?) Which was actually part of a two year program where they actually, they give you a studio and you have access to people in the art world, mostly in Belgium, other artists or curators, or directors and stuff. So after the [HISL?] I didn't know whether to stay in Belgium or to go back to America and I actually did go back to America but some stuff happened so for now I'm still in Belgium. I'm in Antwerp now.

[music]

jb: I guess I also wanna ask: how has moving to Europe changed y9our art practice? And if so, how did it change it?

tds: That's a good question. When I look back at my body of work, the work I've produced, it was always kind of changing. Because I was trying to experiment with different media and usually the thoughts were always the same. But I chose to come to Western Europe because I needed that space of reflection somehow. Just to not only think about who I am or the country I came from, but just space.

I had this Euro-centric idea when I was in the States that I have to go to Western Europe because they must know their stuff. You have the Italians with the high renaissance, or the basic architecture or art history, or even architecture history classes I took at Berkeley always revolved around Western Europe somehow. I mean, it did kind of touch up on the Asias and the Middle east, and a little bit on Africa, not much about South America at all, but it was really Euro-centric.

So I thought "OK, that must be where I should go. They must know better somehow." It's funny because even without trying, when I meet people they say, "Ah, your art looks very American or very Californian because there's so much colour in it."

And um, how has my art changed? Hmmm it just always continues to change. I think if anything, I still, my mind is still in America. Even when I was getting critiqued over here, a lot of the issues I was trying to examine were American issues. So it was kind of hard to get feedback because there aren't many Americans or people from the Americas to give me feedback that I needed at times. But also that's fine because it's something larger.

For a while I wanted to examine my own problems or things I was wondering about. I examined ti in my art but also after a while, it was like, it's kinda. it's boring, I'm not actually interested in it because if I were someone else I wouldn't be interested in it, if that makes sense. Because everyone has a story, but the story doesn't always have to be heard, you know? So sometimes I think, "Ah yeah, my story, actually, pshhh, if I was someone else I wouldn't wanna hear it."

What really makes me interested in other humans is how they maintain their humanity, how they overcome things. But how they do it in their own exuberant way. Because for instance—I'll make it quick—there's this guy named CorlaPandit, and he was this supposedly really exotic piano player who had televised television broadcasts of him playing piano on TV in the '50s, I think. But it turns out this guy, CorlaPandit, who had a head wrap and a jewel on his forehead, he said he came from somewhere in India, at that time, it was accepted in America because like, "Oh this exotic guy, who knows where India is?" I mean, people weren't used to it.

So he introduced to this large audience, mostly homemakers at home in the afternoon, he showed them this exotica music. He maintained this practice until the passed away. He was even in the Ted Burton film Ed Wood. But it turns out CorlaPandit wasn't Indian! He totally falsified this. Him and his wife, she was a worker for Disney, they made this persona up for him to get jobs. He was actually a Black man! Um, somewhere from Missouri or something. Roland....Brown or something? Red, reed, Brown?

He adapted this persona because as a black man in the US, there was this thing called the one drop rule: if you had any drop of Black blood you would be considered Black, even though you might have blond hair and blue eyes, if you have any Black history, then you, there could be ways to discriminate against you. So when this guy went from Missouri to Hollywood, he could not play as a Black man. So he changed his name to like, Juan Rolando, to be a Latino, so he can at least join a union and play music and have gigs and make money.

But eventually, him and his wife, they made this persona. And as an Indian man, he was able to show his talent. And I think that's just like a really amazing story. I mean not only was he talented but he found a way to go through a system. And it could also be a little bit offensive because yeah, it's offensive to people who are Indians. But I think yeah, that's a great story. He went through oppression but he found his way around it. So I find these stories amazing. So many things inspire me, too. But yeah, being in Western Europe, how does it change my artwork? I also learned that, for me it was like finding out how do people operate, which is the same anywhere. But like, are people funded by the government, do they get grants, or are they represented by galleries, or do they open their own spaces? Like how do people exist as artists. And I was curious because there seemed to be a very accessible, quick artist community in the places that I've been able to live here. In the Netherlands and in Belgium, somehow.

jb: So you found your art community pretty fast?

tds: Well, um, it took a while. But like when you know someone and they accept you, you join other communities. Or you meet a nice person. A lot of big things that have happened to me have been through other women artists or women curators and stuff like that. But I guess my point is that for me when I was in the States, I dunno, somehow I didn't know, I couldn't understand how the art world worked.

The art world isn't just like the commercial, capitalistic side. There's all these other things, too. But I didn't know how it operated, I didn't know who did it or how it ran, or how museums ran, you know, if you show your stuff there, they're not responsible for sales and all that stuff. So just going over to Western Europe it was just really quick for me to like—OK, yeah, some artists are really great at selling themselves and they can live that way. But it's a small percentage. You have to earn a lot of money and half of it goes to taxes. So how do other artists do it? Some of them become teachers. But it's, it's everywhere and stuff. But it seemed more accessible. Like, I could find out quicker how it works. I'm still learning, so.

jb: You mentioned earlier that your mind is still in America?

tds: Yeah, at times, yeah, unfortunately, yeah. In America sometimes but like actually it's also here. But a lot of the things I was trying to figure out because of my family's history, of them migrating around the world because of economic reasons, for hundreds of years. My dad comes from China, from Shanghai, but he's, Chinese, but part Portuguese and Dutch because of trade, of course. When you think about it, it's like, Yeah, China was opened up. And through religion and trade. So you have the Dutch also going over there. I mean, what explains my father's grandmother having red hair? Red haired woman in China? But yeah, it was actually a very cosmopolitan place.

My mom's side is mostly descended from African slaves, with Native American blood. And my mom's father was half English and stuff. So for me it was always difficult: how do I make sense of this for myself? Because what culture do you identify with, somehow? We're American but we're also all these other types of people. And I was trying to figure that out in art. But I didn't want to ever draw a line and say, "I'm gonna make art about my Black experience" or whatever, because there actually was none. It's a mixture of everything.

And the reason why I didn't wanna draw a line in anything and [I] focus more on objects—and objecthood—is because as soon as you say that you are this, then you, it's defining yourself based on what someone else is not. And sometimes that's very exclusive, it excludes other people. So for me I'd rather not really say it but just examine this through objects.

That's how we all exist. I mean, we're surrounded by things that humans make or that occurs naturally. But we have relations with objects, also. And for a while, I used to think that it's really interesting to look at forms because there's all these histories within it. And with humans also our behavior in a way is a form. It kind of shows where you're coming from somehow, how you are. Or your mental state.

[music]

tds: My father, along with his parents, he emigrated. And this is interesting as well, because a lot of us kids, the third generation, we're all doing creative things. And it's something that John Adams, who was a former President, he wrote to his wife Abigail Adams, "I must study warfare in order for my sons to study, like naval architecture and engineering, in order for their sons to study tapestry and painting." And, um, sewing and all that stuff.

It takes three generations finally to crawl out of poverty or to assimilate into another land, and to allow for your grandchildren to make art. To get to the point. Because someone has to crawl out of poverty, someone has to make money and get an education and then finally you're free, the next generation can make stuff. To think, to be able to have that time to think, and then make stuff.

[music]

tds: And actually on my mom's side, her father, he considered himself "Coloured" but he was born in England to his English mother, who had red hair, and to a, his Black father. Who came from West Virginia, which was Fayetteville, a coal mining town. That man, my great grandpa, Alfonso Pierce, did not want to work in the coal mines, as a Black man. Or as any man! You don't want to work in the coal mines, it's terrible work, and terrible health effects.

So he went up to Ohio and this is around the turn of the century, the 1900s, to get an education and he decided to jump on a ship and he fled to England where he met my great-grandma. They got married, they had a kid (my grandpa) then they emigrated 1926 to New York, to Manhattan and they lived there and stuff, actually. But it was very difficult because there was the crash of '29 but with Alfonso, I actually googled his name and I found him.

He actually had a patent on making a toy in the '50s and it was really cool! It was like this little rubber band feather contraption that if you pull something it'll fly. But it was so cool to see something from my great-grandfather, still alive, in a US patent, I don't know, system. He was applying for a patent for this toy. Yeah yeah yeah.

jb: it's beautiful. Your fascination for toys comes back!

tds: Yeah, I didn't think of that! You drew a conclusion very quickly, Josie. Thank you very much!

jb: Well I'm not sure if you agree with it. [laughter]

tds: I didn't think of that somehow. Yeah yeah yeah, it's very nice!

[music]

jb: Thanks for joining me on our visit with Tramaine in Antwerp. Remember you can see her work on our website, and you can follow Tramaine on Instagram. Because this episode was, yeah, not only travel to Belgium but also travel through time. And she's been up to some interesting things lately.

sv: Indeed.

jb: Thanks for listening to our show.

sv: It means the world to me.

jb: Who do we have a crush on in our next episode?

sv: In our next episode we have a crush on David Wilson. He has a website:

davidwilsonandribbons.com. But he's not on Instagram. And he also does not have a cell phone. But he's amazing and you can see some work by him on our website.

jb: Speaking of, that's also where you can sign up for our newsletter. You'll get some special perk for signing up for it. But we don't know what yet.

sv: Kisses? Like maybe kisses, air kisses through the air, like [kissing sounds]

jb: Absolutely! Until then, remember to rate and review and subscribe and just generally be nice to us and yourself and everyone.

sv: And follow us on Instagram at artcrush_international

jb: Love you!

sv: Bye!